In the opening section of "The Right to Privacy," to explain why it was imperative to develop new safeguards to shield the family from external forces, Brandeis and Warren took aim at what had already become a favorite target of disapproval, the overly "enterprising press.” Noting that newspapers had begun to employ techniques and technologies that "invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life," the authors railed against the proliferation of sensational stories that played to the lowest appetites:

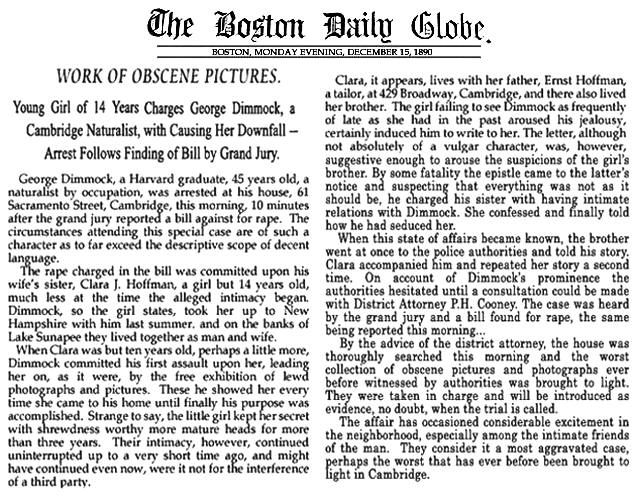

A survey of the suicides, murders, abductions, and sex crimes that crowded the pages of major newspapers during the 1890's lends color to these complaints. In fact, compared to the fatal lovers' quarrels, ugly divorces, and blood-soaked crime scenes that filled the Boston Daily Globe at the end of the nineteenth century, the majority of newspapers in our time seem relatively tame. 10s Here is a sampling of front-page stories from the Globe on February 10, 1890, along with an item on the arrest of Harvard graduate George Dimmock in Cambridge on December 15, 1890, the date of the publication of "The Right to Privacy" in the Harvard Law Review.

While the misfortunes of women figured especially prominently on February 10, suicidal ingénues, wretched harlots, and ravished maidens typically received extensive coverage in the Globe. Moreover, as indicated by the story of George Dimmock's rape of Clara Hoffman, reports on sexual offenses during the Gilded Age usually included the names and addresses of both perpetrators and victims. Although these details were eventually excluded from "all the news that's fit to print" even in the tabloids, the move toward greater reticence did not issue from the conviction that revelations about rape and sexual coercion subvert the dignity of victims, nor did it stem from a concern that such reports oblige girls and women to bear the onus of crimes committed against them. Instead, in the late nineteenth century, commentators such as Brandeis and Warren discouraged public disclosure of these offenses because they conceived of sexual transgressions, not so much as crimes against specific individuals, but as violations of family honor and reputation. In concert with this conception, Brandeis and Warren wrote approvingly of the action per quod servitium amisit, which, in cases of sexual molestation, equates harm done to dependent children with those inflicted on servants and allows parents to collect damages based on the loss of their children's "services." This equation was, Brandeis and Warren admitted, "a mean fiction," but it answered the "demands of society" because it permitted "damages for injuries to the parents' feelings" without actually specifying the nature of the crime. Lest anyone imagine that the inclusion of both parents in the main text implies that this loss of honor pertained to mothers as well as fathers, the footnote to this passage makes it clear that Brandeis and Warren had in mind the way the debauching of a daughter specifically injures the person of a patriarch. The note begins with the observation that the basis of this claim is not the injured child's inability to contribute to the material welfare of her parents: "Loss of service is the gist of the action; but it has been said that "we are not aware of any reported case brought by a parent where the value of such services was held to be the measure of damages." Brandeis and Warren proceeded to recount how emotional harm to the father became the fulcrum of the claim:

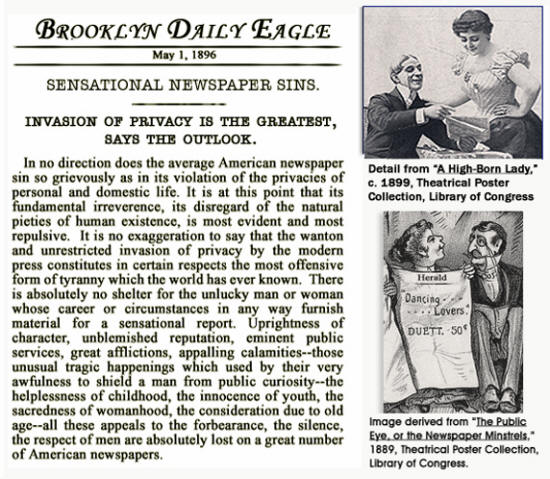

Brandeis and Warren's notion of personal injury in cases of "intrusion by seduction upon the honor of the family" provides insight into the assumptions that guided the Globe's reporting of George Dimmock's crimes against Clara Hoffman. As indicated by the headline, Dimmock was perceived to have caused Clara's "downfall," that is, from the start it is plain that the girl had been damaged beyond repair. However, even though she was only ten years old when the assaults began, Clara was apparently not an entirely innocent victim. For instance, as if to explain how she had allowed herself to be corrupted by Dimmock's "free exhibition of lewd photographs and pictures," the reporter noted that she had "kept her secret with a shrewdness worthy of more mature heads for over three years." Moreover, having practiced her deception for quite some time, she might have continued to carry on the "intimacy" had she not "aroused" Dimmock's "jealousy" and "induced him to write to her." The discovery of Dimmock's letter ultimately led Clara's brother, who is not named in the story, to "charge" her with consorting with Dimmock, thereby forcing her to "confess." While Clara's unnamed brother dutifully notified authorities, the reader is left to speculate about the role of her father, Ernst Hoffman, the tailor who lived at 429 Broadway in Cambridge. Within the context of the late nineteenth century, Ernst Hoffman clearly had the most to lose from the publication of this story, not only because it implied that he had failed to contain his daughter's wayward tendencies, but also because she did not have any separate legal or social identity. Her person, from a legal and social standpoint, was entirely subsumed under his. This is the principle at work in per quod servitium amisit. As Brandeis and Warren observed, in most cases, parents could not cite emotional distress over injury to their children as the basis for a claim, but when an unmarried daughter was despoiled, her father could seek compensation on the grounds that the "dishonor to himself and his family" equaled a personal physical attack. In other words, viewed from the angle adopted in "The Right to Privacy," when Clara Hoffman's downfall was reported, her father became, in a sense, Dimmock's primary victim. Ernst Hoffman had not, by this account, committed any crime, but he was bound to be held responsible for his daughter's undoing. Consequently, from Brandeis and Warren's perspective, there could be no justification for identifying him or his daughter in public. After all, they asked, if publication of personal information could be prevented when it imperiled a man's business interests or financial standing, why should it not be suppressed "if it threatened to embitter his life?" 2p In line with Brandeis and Warren's contention that accuracy did not legitimize invasions of the domestic sphere, "The Right to Privacy" focused, not on the truth or falsity of newspaper coverage, but on the ways in which the circulation of seamy details about sexual relations degraded public discourse. Along with a host of like-minded critics who, ironically, sounded off in newspapers throughout the 1890's, Brandeis and Warren condemned the tabloids for whipping up the public's morbid enjoyment of other people's pain.

E. L Godkin, whose essay, "The Rights of the Citizen to His Reputation," was twice praised in "The Right to Privacy," shared Brandeis and Warren's consternation about the demoralizing effects of the popular preference for gossip over significant news. Like Brandeis and Warren, he condemned the mass circulation of personal information both because it undermined public discussion of broader issues and because it turned the mortification of individuals into profitable entertainment. Directly anticipating Brandeis and Warren's contention that the gossip industry deprived men of any escape from the pressures of modern civilization, Godkin recalled Coke's dictum that "a man's house is his castle" in order to show that the right to privacy had long been recognized as a fundamental principle of law. Likewise, just as his more famous contemporaries portrayed modern methods of publicity as a threat to the integrity of every man's "inviolable personality," Godkin defined freedom from public scrutiny as an inveterate right of the head of every family.

Godkin, Warren, and Brandeis all reached back into history to prove the venerable heritage of the right to privacy, and all three stressed that the conditions of modern industrial society made it necessary to invent new protections for this ancient right. On one hand, they argued, the progress of civilization had deepened men's delicacy of feeling, making them more susceptible to the pain of public exposure. On the other, technological development had vastly increased the speed and scope of the circulation of personal information. Given the transformation of the newspaper industry by new and constantly improving technologies such as the telegraph, the camera, and the rotary printing press, Brandeis and Warren warned that "numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that "what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops." 2p Likewise, Godkin complained that the transmission of stories across the country intensified the pain of publicity because information was spread so quickly over such a wide expanse that men could no longer determine who knew what about their personal affairs. Details that had once been confined to neighborhoods were no longer passed only among local gossips, but had become a "marketable commodity" that, once printed, could be disseminated among complete strangers either a few city blocks or thousands of miles away. As a result, a modern man was apt to fall prey to an anxiety that had never been experienced before, namely the fear that "everybody he meets in the street is perfectly familiar with some folly, or misfortune, or indiscretion, or weakness that he had previously supposed had never got beyond his domestic circle." 12s Despite profound reservations about fighting invasions of privacy in open court, Godkin clearly agreed with Brandeis and Warren's designation of newspaper gossip as the greatest scourge to the civility of American society. In an earlier essay on libel, he commented that the remarkable expansion of the newspaper industry throughout the nineteenth century required "one to admit that to no other art has the progress of invention and the growth of population made such additions as to the art of holding persons up to public odium or contempt." 13s Given the threat to individual security and common decency posed by these violations of domestic tranquility, Godkin provided an almost word-for-word preview of the arguments advanced in "The Right to Privacy." "Nothing," he maintained, "is better worthy of legal protection than...the right of every man to keep his affairs to himself, and to decide for himself to what extent they shall be the subject of public observation and discussion." 14s Go to page 3, The Mysteries of Passion

|