|

Published in 1890, "The Right to

Privacy," by Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren, remains widely regarded as the most influential law

review article in American history. While it would be

impossible to summarize here even a portion of the commentary,

criticism, and praise that have been heaped on Brandeis and Warren's

essay over the past century, we may draw three conclusions

about its contribution to the configuration of the public/private

dichotomy in American legal and social thought:

First, the perspective adopted in "The Right to Privacy" was

highly interventionist, however much that fact has been buried

in references to "the right to be let alone." Judges and other

public officials in Brandeis and Warren's day may have chosen to

look the other way in cases of sexual assault and household

violence, but the entire purpose of "The Right to Privacy" was

to extend the reach of the legal system so that men would not

have to fend for themselves in avenging injuries to their

feelings and reputations

Second,

as evidenced in Brandeis and Warren's approval of legal fictions

to guard against the disclosure of sexual crimes, as well as

their perception of newspaper gossip as a blight on common

decency, "The Right to Privacy" can be most accurately

described, not as a call for the

state to step back from the private sphere, but as an approach to

public discourse that upheld the threat of litigation as a means

to encourage the press and other people to

practice self-censorship.

Third,

the contrast between Brandeis and

Warren's appeals to tradition and history and first-wave

feminist calls for a transformation of both the public and

private spheres shows that "The Right to Privacy" can be better

understood as an effort to cement social conformity than as a

defense of individual freedom.

More generally, setting "The Right to

Privacy" against the backdrop of the cult of domesticity in the

late nineteenth century allows us

to understand more clearly how the public/private dichotomy unfolded in

later years. The historical forces that fomented

twentieth-century concerns about privacy are far too complex to capture in a few

paragraphs. It is, however, obvious that Brandeis and Warren's views on

the sanctity of the home took hold in part because they

dovetailed so seamlessly with the privatizing tendencies of

industrial capitalism. Although its authors railed against the

vulgar exhibitionism of commercial culture, "The Right to

Privacy" confirmed the commercial messages that were quickly

becoming ubiquitous in American life. The idea that every

man's home is his castle is, after all, exceedingly familiar, not

because lawyers like to quote Lord Coke, but because it has been so

tirelessly repeated in so many forms by the advertising industry.

Indeed, if there was one directive that middle-class Americans received more

often than any other during the twentieth century, it was that the

greatest joys and pleasures can be had within the properly

furnished, smartly equipped, tastefully decorated, fully secured,

and well-stocked private home. 52s

However much

Brandeis and Warren may have wished to

shield the home from commercial modernity, the cult of

domesticity was and still remains a mother lode for American business.

Construction companies such as Aladdin, which offered

every man his own readymade "Castle" for under $500 in 1909, flourished by

helping to install homeownership as a standard component of the

American dream. Slews of others prospered by pointing out

the breathtaking wonders that right-minded people enjoy within

safety, comfort, and, above all, privacy of their homes.53s

Elevating popular preoccupation with domestic relations to new heights,

advertisements for appliances, furniture, clothing, decorative

objects, and other must-have merchandise reinforced Brandeis and

Warren's vision of the home as the place where individuals find

self-fulfillment within the bosom of their families.

Paradoxically, however, the advertisers conveyed this message mainly

by placing private life on display, flooding American culture with

images of intimacy, and turning previously unmentionable

topics such as ladies' underwear and male impotence into subjects of

social discourse. 54s

The avalanche of ads that paid tribute to

the joys of domesticity boosted the value of privacy both

as an economic selling point and as a social ideal.

At the same time, the commercialization of the private realm made

the notion of the home as a haven increasingly hard to sustain.

After all, the telephone, radio, television, and, most recently, the Internet,

blurred the boundaries between public and private, not simply by

bringing outside forces directly into the domestic circle, but, more

specifically, by filling it with anxiety-inducing messages about

the need for additional spending. Thus, in the course of the

twentieth century, as the line between the marketplace and the home

dissolved in a barrage of commercial exhortation, and consumerism became

an organizing principle, if not the lifeblood, of the average

American family, economic expansion conspired with possessive

individualism to make the home seem more like an incomplete

collection of

commodities than a refuge from the outside world. Indeed,

in view of the nearly identical houses crammed with nearly identical

objects that currently crowd the American landscape, it seems more

realistic to define the American home as an involuntary response to market

forces than as a shelter from extrinsic pressures, expectations, and

trends.

The popular conception of the home as a refuge is

misguided, not only because it belies the extent to which commercial

forces have shaped the private sphere, but also because it implies

that we are somehow more free behind closed doors than we are on a

public highway. However, in spite of all we've been told about

which products will allow us to kick back, relax, and be ourselves

in private spaces, it is hard to find any instance in

which we could realize significantly greater freedom by shutting

ourselves off from the wider world. In fact, apart from being able to expose more

of our bodies, which is the governing principle behind

prohibitions against publicly performing or describing certain bodily functions

and sexual acts, we have no more liberty in

private than we do in public.55s

Not only must we

obey almost all the same laws on both sides of the public/private

divide, but it would certainly be a stretch

to imagine that we may somehow evade social expectations, moral strictures,

and ethical considerations simply by drawing the shades.56s

Without denying the relief

that may come from avoiding public scrutiny, we can see how the

definition of the private realm as an area

in which human beings may operate with some greater degree of

autonomy has muddied our comprehension of the issues most closely

tied to the right to privacy. Abortion is, for example, not

more or less private than brain surgery. Like other types of

medical treatment, it is subject to public regulation and can only

be carried out with the assistance of people who are licensed and

supervised by the state.57s

Likewise, it has become less dangerous to

engage in homosexual activity, not because this behavior is now

located in the private realm, but because it has been decriminalized.58s

Indeed, it makes more sense in the cases of abortion and homosexual

sodomy to recognize that these activities have always taken place in

private, and it was only public intervention, mainly in the form of

grassroots activism and legal rulings, that enabled at least some individuals to

access abortion services or to engage in homosexual relationships without having

to fear retribution from either private actors or the government.

It is, moreover, helpful to remember that

the space originally defended in "The Right to Privacy" and later

defined, however vaguely, as deserving of legal protection was not the

home or the family as a lived reality, but an idealized and largely

commercialized vision of

domesticity. As a result, the "zone of privacy" that was mapped

out hazily in court rulings and in legislation passed

throughout the twentieth century has, for the most part, been legitimized only

to the extent that it seemed to conform to accepted notions

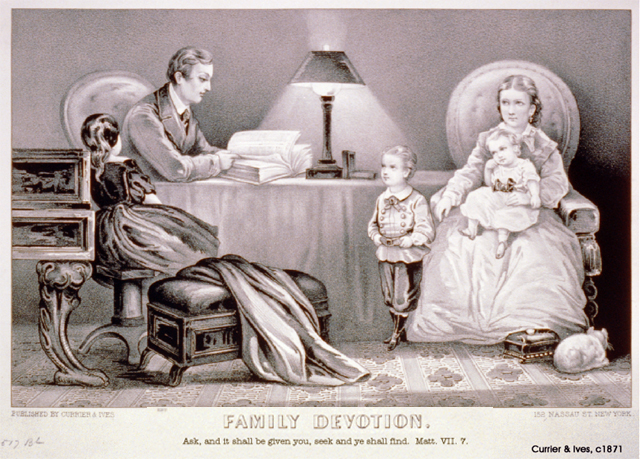

about the normal bourgeois family. It is, for example, no accident that

William O. Douglas's tribute to marriage in

Griswold v. Connecticut so closely resembles the sentimental

images of domestic order that have permeated American culture since

the heyday of Currier & Ives:

We

deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights - older

than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage

is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring,

and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association

that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not

political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social

projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any

involved in our prior decisions. 21p

Without dismissing the appeal of these

sentiments--or denying that the traditional dream of domesticity has

lately been pervaded by same-sex couples--it is interesting to note

that Douglas offered this salutation to marriage during an era when radical and even

not-so-radical feminists were echoing Woodhull and Gilman's critique

of the bourgeois family as an enervating cage.59s

Douglas's concept of "bilateral loyalty" may be viewed step ahead

of the paternalistic approach to domestic relations taken in "The

Right to Privacy." Nonetheless, his commentary on the sanctity

of marriage harkens back to Brandeis and Warren's efforts to situate

moral reality inside the apolitical confines of the ostensibly happy

home. In this respect, Griswold

mimicked Brandeis and Warren's response to the

nineteenth-century struggle for women's rights. As we have seen, they responded to the women's

movement, as well as the technological transformations of their

time, by trying to carve out an area of life that would remain

untouched by commercial pressures, social ambitions, and political

disputes. Similarly, at a moment when feminists shouting, "The

personal is political!" had just begun to gather in public

demonstrations, Douglas asserted the right to privacy as a means to

separate the domestic realm from the social, commercial, and political

"projects" that preoccupied the world outside the family.

60

The poetic commentary contained in the

Griswold decision allows us to see that Brandeis's contribution

to the elevation of the right to privacy in American legal culture

cannot be coherently tied to libertarianism or to a philosophy of

limited government. Instead, as shown in Brandeis's approach

to government regulation both before and during his tenure on the

Supreme Court, his definition of privacy as the premier value of

civilized society translated into a sometimes highly intrusive

dedication to calling on government to guarantee the priority of the

family over everything else.

For example, in his famous

brief in

Muller v. Oregon (1908), Brandeis marshaled social

statistics to show that the biological destiny of women as wives and mothers supersedes their

rights as individuals. Advancing the same protectionist

approach that he and Warren had adopted in "The Right to Privacy,"

Brandeis maintained that women needed to be secured from economic

exploitation so that they could properly discharge their natural

familial obligations. His brief was accordingly designed, not to promote the

well being of workers in general, but to legitimize

gender discrimination by forcing employers to take heed of the duties and disadvantages attached to

womanhood. Just as the Court in earlier cases had singled out women's bodies as

deserving of special protections, Justice Brewer

drew on Brandeis's work to argue that the physical drawbacks of

being female, as well as the burdens of maternity, legitimized

treating "woman as an object of public interest and care." In

other words, even though there might at first glance seem to be some

inconsistency between Brandeis's exaltation of privacy

and his case for government regulation of female labor, both were

interventionist efforts to safeguard family relations, and

both endeavored to achieve that goal mainly by shielding the female body,

in Brewer's words, "from the greed and passion of man." 13p

The paradoxes that have arisen in the

historical trajectory set off in "The Right to Privacy"

make sense when we consider their starting point. Writing in

reaction to rapid social change, Brandeis and Warren's main

objective was to discover legal instruments that would enable men to

preserve their masculinity by screening themselves and their

dependents from the ever more intrusive pressures of late

nineteenth-century industrial society. True to the progressive

spirit of their age, as well as their conservative commitment to

domestic tranquility, they found in the common law precisely the right tool to

allow modern man to carry out this ancient prerogative,

"a weapon...forged in the slow fire of the centuries, and to-day fitly

tempered to his hand." 2p

In line with these chivalrous sentiments, and in keeping with the valorization of the domestic

sphere in subsequent decades, the lasting legacy of "The Right to Privacy"

has been not to enlarge individual liberty, but to outline a legally sanctioned

and socially acceptable context in which men and women could meet their moral obligations by conforming or, at least, seeming to

conform to conventional family roles.

|