|

Getting Up With Fleas: "Mad Dog" Robinson Bit by Archdiocese

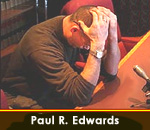

Here's how Robinson backed himself into this journalistic jam: In August, after the Archdiocese declared that the files of both Foster and Cummings were clean, Robinson apparently decided that Foster, a leading canon lawyer who had assembled a top-notch legal and public relations team, was the perfect vehicle to show that the Globe would champion the rights of priests who had been falsely accused. Consequently, employing the same tactics that he had used to assault the credibility of historian Joseph Ellis, civil rights leader Paul Parks, and former vice-president Al Gore, Robinson defended Foster by assailing Edwards as a "teller of tall tales" whose "long history of embellishment" raised grave doubts about truth of his allegations. Robinson's multi-article blitzkrieg was so effective that Eric Parker, Edwards' lawyer, withdrew his client's lawsuit against Foster and Cummings, and the case was dismissed less than a month after it was it was filed.However, in the aftermath of Robinson's onslaught, Church officials delayed Foster's return to his position as judicial vicar. In fact, after announcing that Foster could return to active status, the Archdiocese suddenly removed him again. In the course of this confusing process, the Spotlight Team rallied support for Foster in a series of articles: Priest says he is 'disheartened' by church silence, Church faulted on slow pace of priest abuse probes, and Archdiocese eyes more legal rights for accused priests. Likewise, in an editorial, A False Accusation, the Globe lamented Foster's "ordeal" and worried about the rights of priests who were subjected to false charges.Meanwhile, outrage percolated throughout the Catholic press. For example, The National Catholic Register wondered why Foster's exoneration had been so long postponed: "[Foster's] two suspensions are the result of sexual-abuse allegations so evidently baseless that the civil courts have dismissed them - with prejudice, meaning they can't be

filed again - and the Boston Globe has run detailed exposÚs portraying the

priest's accuser as a pathological liar."

civil courts have dismissed them - with prejudice, meaning they can't be

filed again - and the Boston Globe has run detailed exposÚs portraying the

priest's accuser as a pathological liar."

In keeping with his nickname, "Mad Dog," Robinson himself seemed peeved that his hatchet-job on Edwards took so long to yield results. On September 7, in "Priest says that he's disheartened by Church silence," Robinson observed, "For Foster, the last three weeks have been a nightmare. Edwards, who has a long history of inventing stories, according to many of his childhood friends, went public with his lawsuit on Friday, August 16. Six days later, the Globe report raised serious doubts about the charges against both priests."What seemed disturbing to Robinson and other Globe reporters was not only that Foster had languished for weeks under a cloud of supposedly undeserved suspicion, but also that the Church's refusal to clear Cummings hampered Foster's efforts to clear his name. As Robinson and Globe reporter Steven Kurkjian emphasized in Church faulted on pace of probes, "The archdiocese's failure to pursue evidence in the Cummings case has compromised Foster's ability to counter the allegation against him by pointing to doubts about Edwards's credibility - doubts that have already been publicly aired. Edwards's own attorney abandoned the case and Edwards dropped his lawsuit against both priests after a Globe story on Aug. 27 (sic) raised serious questions about the veracity of his accusations." Like Foster's supporters, the Spotlight Team seems to have assumed that doubts cast on Edwards' charges against Cummings would automatically extend to his case against Foster. Along these lines, Sharon Phinney, who was described by Robinson and Kurkjian as a "witness" --though it's not clear what she might have seen--was quoted in the Globe, ''Obviously, if Paul has made a false claim against Father Cummings - false because the incident could not have happened - then it totally undermines his credibility on what he says about Monsignor Foster.'' Several weeks later, after Foster was reinstated for reasons that have yet to be specified, Foster himself implied that his exoneration should have led to an official resolution of the Cummings case: ''I never heard that they investigated anything in regard to Father Cummings,'' Foster said. ''And yet he has siblings. He has family members. His reputation was put on the line, and he couldn't defend himself. He's dead.''

In stark contrast to the Globe's repeated refusal to correct its previous distortions, Robinson quoted Edwards' new attorney: ''I believe Paul's allegation against Father Cummings, without reservation,'' Carmen L. Durso, who is Edwards's lawyer, said in an interview, noting that Edwards told at least two people about the alleged molestation by Cummings more than a decade ago. ''The fact that there is a second allegation against Cummings certainly adds to [Edwards's] credibility.'' Moreover, having earlier suggested in several articles that Edwards had lied about working as a police officer, lied about his medical condition, and lied about visiting Foster's living quarters, Robinson was forced to acknowledge in the course of his latest piece that Edwards had worked as a police officer, does suffer from genuine paraplegia, and did spend time in Foster's bedroom. However, despite repeated calls from survivors' groups for the Globe to admit its role in promoting public misperception of Edwards, Robinson chose to chalk up his misreporting to his usual sources, an unidentified group of "childhood friends." When the falsehoods promulgated by Spotlight reporters were first revealed in the Herald late last year, survivors immediately asked the Globe to make corrections and demanded that the Archdiocese reopen the Foster case. However, even though Robinson has now offered some incomplete and overdue admissions about Edwards' credibility, it is doubtful that the Globe will ever support a resumption of the Foster inquiry. Whatever excuses Robinson may invent at this point, affidavits in the monsignor's file, along with all of the articles displayed on the Globe's Internet tribute to Foster, show that the Spotlight Team played a central role first in undermining Edwards' lawsuit and then in promoting the monsignor's still inexplicable return to his post.

Given the Globe's participation in shutting down the first and only investigation of any of the 24 active priests accused this year in the Archdiocese of Boston, it is hard to imagine that the paper would persist in promoting its previous views of the way the charges against Cummings reflect on those against Foster. Indeed, it is likely that Spotlight reporters will switch to the position of the Rev. Christopher J. Coyne, an archdiocesan spokesman, who said, "The allegations by Paul Edwards against Monsignor Foster should stand or fall on their own, regardless of allegations against another priest." Coyne's implausible perspective is, of course, the only stance available to Archdiocese officials since they have known all along about Cummings' sordid past. The Globe, on the other hand, built its case for Foster by pointing to Cummings' ostensibly unblemished history. After Foster was finally reinstated, Robinson and Spotlight reporter Michael Rezendes accordingly took the Church to task, complaining that "Church investigators had not sought interviews with any of more than a dozen people who gave the Globe information that appeared to exonerate Cummings, even though their testimony also cast doubt on the credibility of Foster's accuser." Since Foster's supporters turned out to be dead wrong about Cummings, it is certainly reasonable to expect the Globe to publish point-by-point corrections of the misinformation they spouted in interviews with Spotlight reporters, especially since it's obvious now that the Spotlight Team published what they said without bothering to check any facts. Sadly, Globe editors, reporters, and the ombudsman have all elected to ignore survivors' calls for for the Spotlight Team to repair its errors. More specifically, rather than fixing the mess that he created, Robinson has chosen to blame Foster's supporters for feeding him sophomoric fibs about Edwards and to fume at the Archdiocese--hardly a bastion of integrity--for giving him the go ahead to launch an all-out offensive against the alleged victim. As a result, the public remains almost entirely uninformed about the role of the Globe in the withdrawal of Edwards' lawsuit; the Archdiocese has refused to reopen the Foster investigation; Edwards' reputation has yet to be restored; and Robinson is crying to survivors about having been deceived.

As for Robinson's journalistic techniques, it

should be noted that his usual specialty is tearing down more or less

public figures such as Joseph Ellis, a relatively harmless and widely

respected scholar whose worst sin was lying about himself. In this

case, on the other hand, Robinson embellished facts, stretched the truth, and told

tall tales about a markedly defenseless man in a wheelchair who wa Foster was, by the way, also backed by Church insiders such as Ned Cassem, a member of Cardinal Law's blue ribbon commission on sexual abuse. Cassem, a psychiatrist who never met Edwards, signed an affidavit prepared by Fosters' handlers that described Edwards as a "sociopath" and a "psychopath" and also advised the monsignor to wear a "Kevlar vest." and "learn to use a gun." Cassem's affidavit was so outrageous that even the Church investigator, the Rev. Sean Connor, suggested that it was "fraudulent." Robinson may not be as out of touch as Cassem. However, like Cassem, he seems to have refused to recognize who was the victim in this debacle, insisting in article after article that Edwards was a complete liar whose unsupported allegations had besmirched the reputation of two revered priests. Moreover, like Cassem and the Church establishment, Robinson apparently imagines that the first order of business in investigating sexual abuse allegations is not to examine the conduct of the accused, but to rifle through accusers' personal histories in order to unearth every last speck of information that might be turned against them. Imagine that you are a victim who has yet to come forward. Having seen what the Church and the Spotlight Team did to Paul Edwards, would you risk speaking out? Although there is talk of a libel suit against the Globe, the outcome of the Foster case cannot be foreseen at this point. However, the Spotlight Team's ruthless undoing of Edwards, along with the hostile insensitivity that its members have aimed at many other victims, has produced one unassailable verdict, which is that the Globe's decision to put "Mad Dog" Robinson in charge of reporting the intimate and complex stories that are the soul of this scandal was a horrible mistake. |

Last summer, after Paul R. Edwards accused the

late Rev. William J. Cummings and Monsignor Michael Smith Foster of

sexually molesting him during the 1980's,

Last summer, after Paul R. Edwards accused the

late Rev. William J. Cummings and Monsignor Michael Smith Foster of

sexually molesting him during the 1980's,  Unfortunately for both the Globe and Foster, new

revelations about Cummings have thrown this logic in reverse.

Contrary to the previous declarations of Church officials, Cummings has

been subject to multiple allegations. On September 3, the very day that the Globe's campaign against Edwards compelled him to drop his

lawsuit, the Archdiocese received another lawsuit against Cummings, which accused the

priest of molesting a 10-year-old boy in a church in Somerville in

1982. Once that lawsuit came to light in January, Robinson could not wriggle out of

reporting information that substantiates Edwards' claims.

Unfortunately for both the Globe and Foster, new

revelations about Cummings have thrown this logic in reverse.

Contrary to the previous declarations of Church officials, Cummings has

been subject to multiple allegations. On September 3, the very day that the Globe's campaign against Edwards compelled him to drop his

lawsuit, the Archdiocese received another lawsuit against Cummings, which accused the

priest of molesting a 10-year-old boy in a church in Somerville in

1982. Once that lawsuit came to light in January, Robinson could not wriggle out of

reporting information that substantiates Edwards' claims.

Anyone who doubts where Robinson & Company's

loyalties lie has only to consider the facts that have yet to be reported

in the Globe. These include Foster's remarkable assertion that he cannot

recall if Edwards ever told him of the Cummings

rape. That Foster, a widely celebrated canon lawyer who is supposed

to advise the Archdiocese on sex abuse cases, has, in his own words, "no

clear recollection" of a conversation in which his former friend described Cummings'

attack is not merely astonishing on its face, it contradicts the statement

Foster made to the Church investigator, in which he "categorically denied"

having any knowledge of Cummings' sexual misconduct. This

inconsistency, along with Foster's decision to let stand what he knew to

be false information reported in the Globe, as well as his

threats to sue Edwards for defamation--even though the Archdiocese forbids

such actions--along with his unique contention that, contrary to

Archdiocesan rules, his residence at Sacred Heart was an "open rectory" in

which

Anyone who doubts where Robinson & Company's

loyalties lie has only to consider the facts that have yet to be reported

in the Globe. These include Foster's remarkable assertion that he cannot

recall if Edwards ever told him of the Cummings

rape. That Foster, a widely celebrated canon lawyer who is supposed

to advise the Archdiocese on sex abuse cases, has, in his own words, "no

clear recollection" of a conversation in which his former friend described Cummings'

attack is not merely astonishing on its face, it contradicts the statement

Foster made to the Church investigator, in which he "categorically denied"

having any knowledge of Cummings' sexual misconduct. This

inconsistency, along with Foster's decision to let stand what he knew to

be false information reported in the Globe, as well as his

threats to sue Edwards for defamation--even though the Archdiocese forbids

such actions--along with his unique contention that, contrary to

Archdiocesan rules, his residence at Sacred Heart was an "open rectory" in

which  s

up against a powerful member of the Church hierarchy who had at

his disposal an organized group of supporters, four lawyers and a public

relations firm.

s

up against a powerful member of the Church hierarchy who had at

his disposal an organized group of supporters, four lawyers and a public

relations firm.