Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Body Issues

Today we're going to talk a bit about the bodies that appear in Frankenstein. First, I thought that we should have some historical and cultural context for Shelley's time regarding a variety of issues related to the body, including 1) Galvanism, 2) Anatomy/Surgery/Dissection, and 3) Phrenology/Physiognomy.

1) Galvanism: The "Science" of Electrifying Dead Bodies

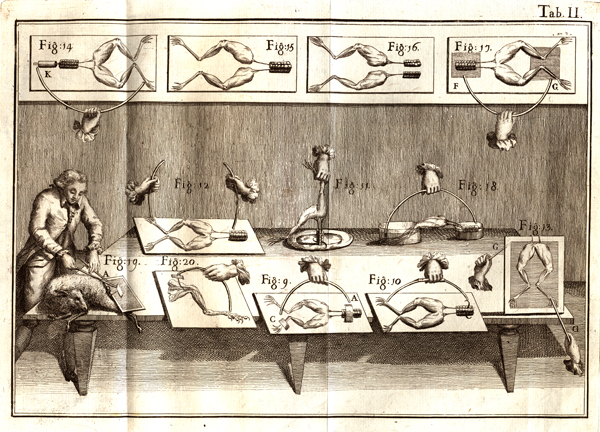

During the 1790s, Italian physician Luigi Galvani demonstrated what we now understand to be the electrical basis of nerve impulses when he made frog muscles twitch by jolting them with a spark from an electrostatic machine. When Frankenstein was published, however, the word galvanism implied the release, through electricity, of mysterious life forces. "Perhaps," Mary Shelley recalled of her talks with Lord Byron and Percy Shelley, "a corpse would be reanimated; galvanism had given token of such things."

Illustration of Italian physician Luigi Galvani's experiments, in which he applied electricity to frogs legs; from his book De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari (1792).

image and info from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/frankenstein/galvanism.html

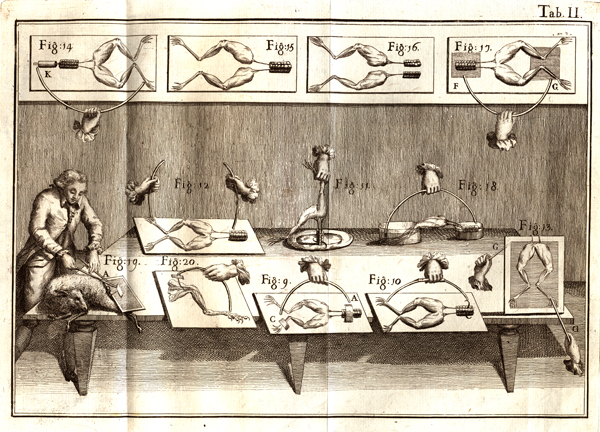

image: Galvani's nephew, Giovanni Aldini, extended experiments to cows and human cadavers (two volumes on Galvanism, 1803, 1819) : http://users.dickinson.edu/~nicholsa/Romnat/hs~romnat1.htm

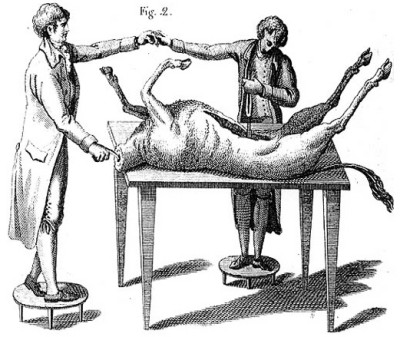

A Galvanized Corpse Cartoon (1836)

Artist: Henry R. Robinson

Galvanism captured popular attention on both sides of the

Atlantic. In this 1836 American political cartoon, Jacksonian

newspaper editor Francis Preston Blair rises from the grave

after receiving a jolt from a galvanic battery.

text info from http://www.nlm.nih.gov/news/franken.html

image from http://www4.gvsu.edu/pozzig/european_civ2/images/images/galvanized%20corpse.htm

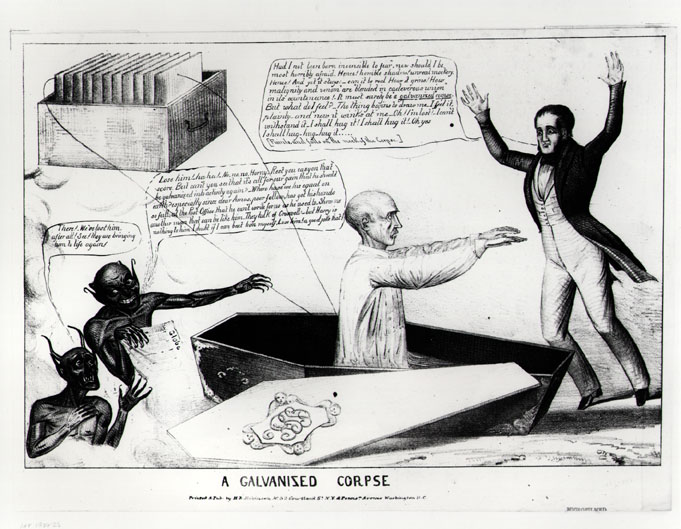

2) Anatomy, Surgery, and Dissection

Victor explains: “I collected bones from charnel-houses [. . . .] The dissecting room and the slaughter-house furnished many of my materials” (54 – 55). During Shelley’s time, the use of dead bodies from dissecting rooms and slaughter houses would have called up criminal connotations, both because the dead bodies of criminals were being used for dissection and medical experimentation, and because body snatchers were committing further crimes by stealing bodies from graves. As if the thought of the creature being formed from the parts of dead bodies wasn’t horrifying enough, the body parts either belonged to the worst criminals of the day, or they were stolen by criminals, in either case leading to the perception of the creature’s body as criminal even before it committed any criminal acts.

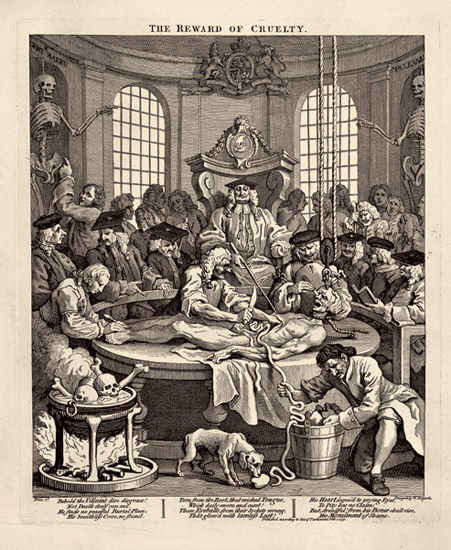

Fear of dissection was a preoccupation throughout the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, particularly evidenced in popular images of the day, such as William Hogarth’s 1751 print, “The Reward of Cruelty,” fourth in his series of four prints entitled The Four Stages of Cruelty.

image from http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/hogarth/modernmorals/fourstagesofcruelty.shtm

Hogarth's series of images were widely reprinted throughout England, particularly at the turn of the century as the cost of printing such images became cheaper. Hogarth’s image portrays the torture of the dead body, as well as a large audience for the dissection, many of whom seem to be quite jolly. In the forground of the picture, a dog eats some of the discarded remains, and apparently human bones are visible in a cauldron. These images – referencing not only the desecration of a body, but also cannibalism display the profound distrust and disgust of the dissectionist’s trade.

The study of anatomy via dissection was intended to improve knowledge and experience of surgeons, however, conditions in the survgery for LIVE patients was pretty much a horrorshow. As Ruth Richardson Explains in Death, Dissection and the Destitute:

· Poor conditions of the surgery wards contributed not only to death due to infection, but also general horror: “Surgery was accomplished on the conscious, screaming patient, by surgeons with dirty overalls, dirty instruments, and dirty hands. The operating table was a slab of wood, channelled to allow the blood to drip down into buckets of sawdust. The patient (referred to by John Hunter as the ‘victim’) was tied down, and held still when necessary” (41). “If the operation was conducted in a teaching hospital, the patient’s agonies would be observed by dozens of students, all exhaling into the atmosphere of the operating theatre, and jostling each other for a view” (41).

· “It could truthfully be said that high hospital mortality was the price paid by the poor both for the advancement of scientific surgery, and the advancing social status of surgeons” (49).

Here's a timeline regarding dissection and grave-robbing:

1752

The Murder Act of 1752 instituted dissection as additional punishment. According to Tim Marshall’s Murdering to Dissect: Grave-Robbing, Frankenstein and the Anatomy Literature, “By design, the law associated dissection with the punishment meted out to the worst offenders; henceforth, dissection was invested with a stigma which was difficult if not impossible to remove in the long term. The ruling elite made dissection an object of dread or superstitious fear – as the Act explicitly stated, an object of ‘further Terror’” (21).

April 1788

A mob of about 5,000 New Yorkers rioted for three days upon discovering that bodies had been stolen from a graveyard.

1789

New York passed a law making it possible for doctors to obtain cadavers without resorting to body-snatching.

Early 1800's

According to Tim Marshall in Murdering to Dissect, “By the 1820s several thousand bodies were required [for dissection] per annum” (21).

1828

"William Burke and William Hare, together with Helen M'Dougal and Margaret Hare, were accused of killing 16 people over the course of 12 months, in order to sell their cadavers as "subjects" for dissection. Their purchaser was Dr. Robert Knox, a well-regarded anatomical lecturer with a flourishing dissecting establishment in Surgeon's Square." (above from http://burkeandhare.com/bhhome.html

1829

William Burke was hanged in Edinburgh for murdering victims by asphyxiation in order to provide cadavers to physicians.

From Richardson: After the discovery of Burke and Hare, “So pervasive was the fear of murder for dissection that the newspapers were peppered with cases of attempted burking, suspected burking, threatened burking, burking in jest, and even in children’s play” (194

1832

Anatomy Act of 1832 (London) passes and expands the legal supply of cadavers for medical research

Additional Info above from http://www.english.upenn.edu/Projects/knarf/Contexts/dissect.html

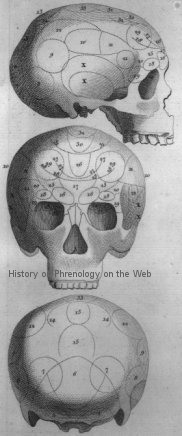

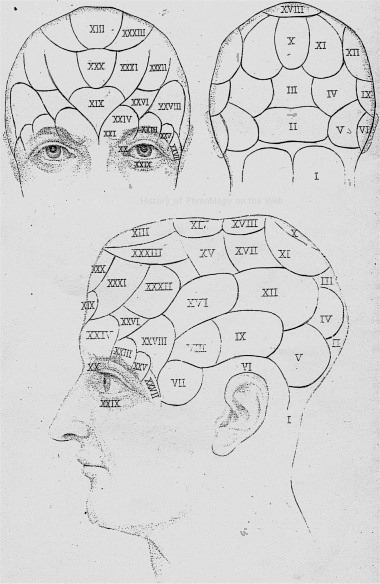

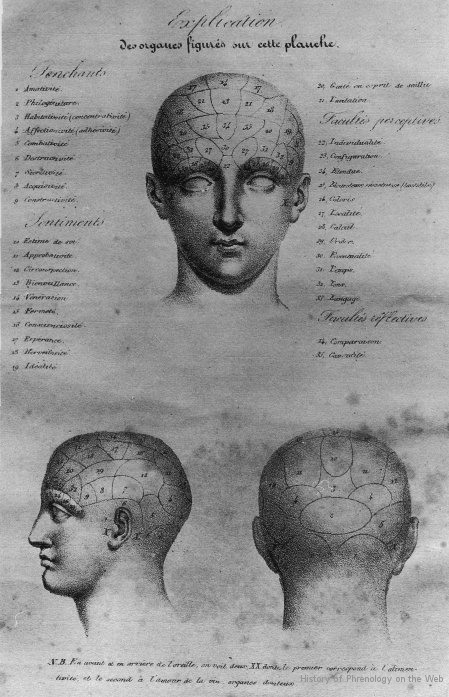

3.) Phrenology & Physiognomy

Phrenology and Physiognomy are pseudosciences that purport to be able to determine an indivdiual's character based on the physical features of the head (Phrenology) and/or the face (Physiognomy).

Developed from the research of John Caspar Lavater, Franz Joseph Gall, and many other prominent minds of the day, these two sciences, while rather quickly debunked by the medical establishment, became quite popular for the general public. The origins of these “sciences” were “in folklore, popular superstition, and religion, in any belief that physical deformity or beauty reflects the state of the soul or one’s relationship with a powerful supernatural being” (Gaull 297).

John Casper Lavater and his followers believed that “the body is inhabited by God and that facial characteristics reflect its character or spiritual nature” (298). His theories were widespread and had gained popular acceptance in 19th century Europe. “Lavater’s vocabulary was popular enough to be incorporated into popular novels, both in prose descriptions and in the illustrations that accompanied them” (337). Particularly important to Lavater’s physiognomy was the connection between human and animal characteristics. For instance, a person’s traits of “lust, greed, [and] secrecy” could be revealed in the face through a “resemblance to goats, pigs, and rodents” (337). Lavater’s connections between animal-like physical attributes and personality traits “influenced the Romantic caricaturists . . . who in turn influenced the way ordinary people, who may not have been familiar with Lavater, viewed public figures that were subjects of these caricatures” (337-8). Even if they were not familiar with the scientific terms, the general public was constantly exposed to the basic concept, since “physiognomy provided the basic vocabulary for cartoons and decorative engravings” (298).

All images from John van Wyhe's excellent resource, History of Phrenology on the Web http://www.historyofphrenology.org.uk/images.html

(the writing here in this section is my own from a couple of articles I've written in relation to the Gothic and Phrenology)

These practices of head- and face-reading were taking on a life of their own in literature, which frequently used the shorthand of phrenology in character descriptions. As Roy Porter explains in “Making Faces: Physiognomy and Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England,” “From the Gothic vogue of the 1790s through to the Victorian social novel, writers insistently depicted their characters through physiognomical eyes” (395). Shelley’s text is an early example of physiognomy being adopted into character description; her characters themselves practice physiognomy, as when Walton describes Victor: “the lineaments of his face are irradiated by the soul within” (31), and when Victor notes that his dislike of M. Krempe is in part due to his “repulsive physiognomy” (50). When, as a child, Elizabeth is found by Caroline Frankenstein in Milan, she is described in strikingly phrenological terms:

Her hair was the brightest living gold, and, despite the poverty of her clothing, seemed to set a crown of distinction on her head. Her brow was clear and ample, her blue eyes cloudless, and her lips and the moulding of her face so expressive of sensibility and sweetness, that none could behold her without looking on her as of a distinct species, a being heaven-sent, and bearing a celestial stamp in all her features. (34)

This is a textbook phrenological study of the face, particularly in its association of fair skin and features with sensibility and morality. Shelley’s descriptions signal phrenological readings, and these readings are apparently correct; Elizabeth is in fact a sweet and nearly angelic character, and M. Krempe is a difficult and unpleasant instructor. While these examples might appear to advocate such body readings, a careful reading of Frankenstein also indicates a decidedly skeptical view of phrenology’s usefulness. The “readings” of the bodies of Justine and Victor, for instance, are wildly inaccurate, showing the very troublesome conclusions that both characters and readers can draw from physical appearances.

Page created by Bridget M. Marshall for the Gothic Tradition in Literature course at University of Massachusetts, Lowell. 2011.