Excerpt from "A Man's Home: Rethinking the Public/Private Dichotomy in the United States"

Gilman stressed that her critique of domestic

relations was designed, not to overturn familial bonds, but to

strengthen the institution of marriage. Consequently, she did not

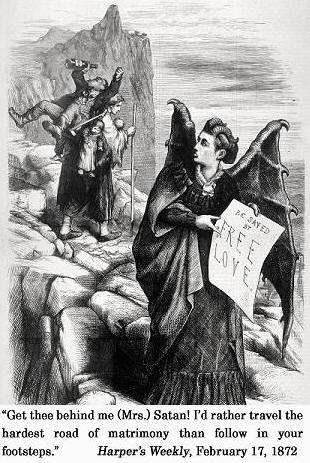

inspire the waves of condemnation that washed over Victoria California

Wo odhull,

the remarkable stockbroker-socialist who earned the nickname "Mrs.

Satan" after she went about the country lecturing on the morally

uplifting benefits of free love. Woodhull, who published the first

English translation of the Communist Manifesto in the United

States, could have counted herself among the "rich socialists" at

certain periods, but she never gained the degree of respectability

granted to more genteel suffragists. Unlike Gilman, who possessed some

social standing as a poor relation of the illustrious Beecher family,

Woodhull grew up in

squalid poverty that was hardly alleviated by her father's sales of a

patent medicine known as the "Elixir of Life." 28s

After marrying Canning Woodhull, an abusive alcoholic, in 1853, when she

was barely fifteen years old, Woodhull supported herself by telling

fortunes, dispensing magnetic healing, and acting in two-bit theater.

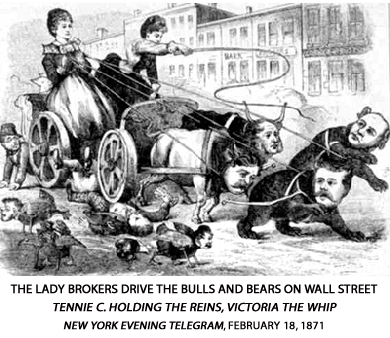

In 1868, having divorced Woodhull, she moved to New York City, developed

a friendship with Cornelius Vanderbilt, and, with his financial backing,

she and her sister, Tennessee--or, as she sometimes called herself,

"Tennie C."--Claflin, prospered as the first women to run a brokerage

firm in the United States.

28s

odhull,

the remarkable stockbroker-socialist who earned the nickname "Mrs.

Satan" after she went about the country lecturing on the morally

uplifting benefits of free love. Woodhull, who published the first

English translation of the Communist Manifesto in the United

States, could have counted herself among the "rich socialists" at

certain periods, but she never gained the degree of respectability

granted to more genteel suffragists. Unlike Gilman, who possessed some

social standing as a poor relation of the illustrious Beecher family,

Woodhull grew up in

squalid poverty that was hardly alleviated by her father's sales of a

patent medicine known as the "Elixir of Life." 28s

After marrying Canning Woodhull, an abusive alcoholic, in 1853, when she

was barely fifteen years old, Woodhull supported herself by telling

fortunes, dispensing magnetic healing, and acting in two-bit theater.

In 1868, having divorced Woodhull, she moved to New York City, developed

a friendship with Cornelius Vanderbilt, and, with his financial backing,

she and her sister, Tennessee--or, as she sometimes called herself,

"Tennie C."--Claflin, prospered as the first women to run a brokerage

firm in the United States.

28s

Woodhull's checkered past did not prevent her from enjoying a short stint as a celebrated leader within the woman suffrage movement. In 1871, capitalizing on connections she had established through her brokerage firm and her newspaper, Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly, she became the first woman to address a joint committee of Congress.4p Steering clear of her unorthodox views on the tyranny of marriage, she urged the congressmen to recognize how little sense it made to deny women, who owned property, paid taxes, and made up the majority of the citizenry, the right to vote. 29s The speech won her widespread support among the suffragists in Washington. However, her sudden popularity soon began to sink after she declared herself as a presidential candidate and attempted to drag Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women's rights advocates toward free love, labor reform, and income redistribution.

Woodhull's recalcitrant radicalism became even

more apparent when she cut her hair short and designed her own

presidential costume, a gender-bending outfit that reportedly included

breaches, a man's shirt collar, and a cravat. Then, in the midst of the

controversy that already threatened to engulf her candidacy, Woodhull's

mother, Annie Claflin, started legal proceedings against Colonel James

Blood, Woodhull's second husband, for threatening her with physical harm

and causing her profound emotional

distress.

During the trial that ensued, press reports on Woodhull's scandalous

past persuaded many of those who had hailed her the new Joan of Arc in

the fight for woman suffrage either to deny her existence or to denounce

her as a harlot. 30s

distress.

During the trial that ensued, press reports on Woodhull's scandalous

past persuaded many of those who had hailed her the new Joan of Arc in

the fight for woman suffrage either to deny her existence or to denounce

her as a harlot. 30s

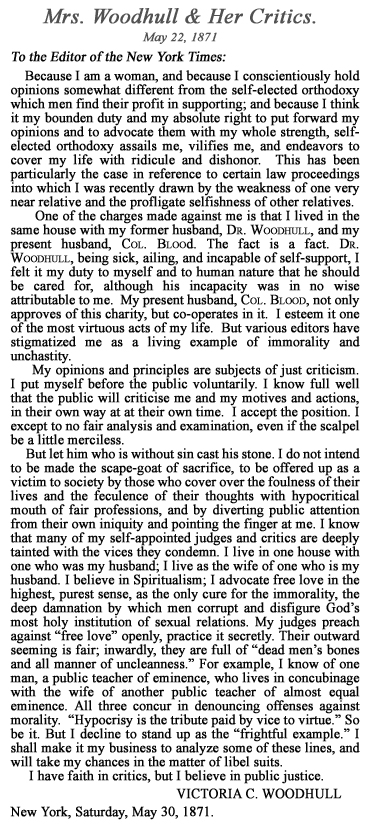

Still confident that destiny had chosen her to replace Ulysses S. Grant, Woodhull decided to redeem herself in the public arena by defending her commitment to free love, confirming that she had, in fact, once divorced and then remarried her present husband, and admitting that she was also living with Canning Woodhull, the husband whom she had divorced before she married Blood. Her unrepentant self-defense, which she set forth in a letter to the New York World and the New York Times, included a warning that she would not allow herself to become the scapegoat of hypocrites who maligned the principles of free love in public while practicing those precepts in private.

Specifically, in a hint that would eventually inspire what one contemporary observer described as the "Greatest Social Drama of modern times," she intimated that she would expose "a public teacher of eminence who lives in concubinage with the wife of another public teacher of almost equal eminence."31s Over the next few years, after Woodhull and others explicitly identified the first public teacher as Henry Ward Beecher, one of the most respected preachers of the age, and the second as Theodore Tilton, a well-known writer and magazine editor, newspaper coverage of the Beecher-Tilton scandal turned the private lives of a handful of New Yorkers into a spectacle that historians have likened to P.T. Barnum's version of the greatest show on earth.32

The complicated story of Theodore Tilton's efforts to bring Henry Beecher to justice for committing adultery with Elizabeth Tilton, the editor's unhappy wife, has been told many times, but Woodhull's reasons for setting the scandal in motion have not been much examined, partly because most historians have assumed that Woodhull circulated her detailed account of Beecher's affair with Tilton in a vengeful attempt to tar him with the same brush that had wrecked her political ambitions. 33s Woodhull may have also wanted to embarrass the minister's straight-laced sisters, Catherine Beecher, a tireless champion of housework and joylessness for women, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, who parodied Woodhull as "Audacia Dangereyes" in My Wife and I, a relatively unsuccessful novel, in 1871. 34s

While revenge almost certainly figured in Woodhull's design, she explained that she felt duty-bound to divulge what she knew about Beecher's affair with Elizabeth Tilton because she hoped that her actions would inspire new respect for the right to privacy. "I take this step deliberately, as an agitator and a social revolutionist, which is my profession," Woodhull insisted. "Messrs. Beecher and Tilton and other halfway reformers are like the border states in the great rebellion. They are liable to fall, with the great weight of their influence, on either side of the contest, and I hold it to be legitimate generalship to compel them to declare on the side of truth and progress." 35s

From Woodhull's standpoint, Beecher and Elizabeth Tilton were morally obliged to defend their romance as a glorious example of exactly the type of spontaneous behavior that people ought to be free to engage in if they were so moved by physical impulse and divine inspiration. While the preacher and his lover would undoubtedly suffer from assuming a leadership role in the sexual vanguard, Woodhull could not imagine how society could advance if such powerful figures dishonestly pledged allegiance to the status quo. On this logic, Woodhull maintained that her invasion of Beecher's privacy was designed as a short-term skirmish in the long-term war to establish individual autonomy as the governing principle of both public and private life.

I hold that the so-called morality of society is a complicated mass of sheer impertinence and a scandal on the civilization of this advanced century; that the system of social espionage under which we live is damnable; and that the very first axiom of a true morality is for people to mind their own business, and learn to respect, religiously, the social freedom and sacred social privacy of others. 36

In line with her grand vision of personal freedom, Woodhull held that the right to privacy applied, not to trivial matters like those cited by Brandeis and Warren, such as whether a man had dined with his wife, but to the most "sacred interests of humanity" in the free communication of love. In Woodhull's view, Beecher and the Tiltons, along with everyone else, deserved freedom from the "system of social espionage," not because public disclosure of their private doings might undermine their reputations, but because they had a perfect right to express their passions whenever and with whomever they might choose within the private sphere.

I believe, as the law of peace, in the right of privacy, in the sanctity of individual relations. It is nobody's business but their own, in the absolute view, what Mr. Beecher and Mrs. Tilton have done, or may choose at any time to do, as between themselves. And the world needs, too, to be taught just that lesson. I am the champion of that very right of privacy and of individual sovereignty. But... I need, and the world needs, Mr. Beecher's powerful championship of this very right... It is not, therefore, Mr. Beecher as the individual that I pursue, but Mr. Beecher ... as my auxiliary in a great war for freedom. 37s

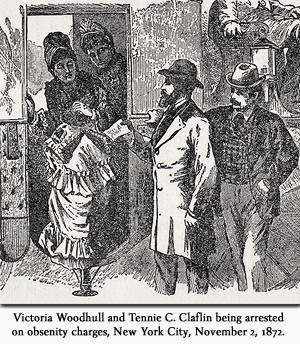

It is doubtful that Woodhull ever sincerely

believed that Beecher would join her campaign for the right of

individuals to act on their desires in private. But whatever backlash

she might have expected, she probably never dreamed that revealing

Beecher's conduct in an article in Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly

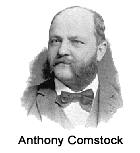

would land her in the Ludlow Street jail. Woodhull's arrest cam e

after Anthony Comstock, who was just beginning his long career as the

self-appointed censor of the United States, realized that going after

her and her sister for publishing such sordid materials would gain him a

great deal of sympathy, both from the public at large and from the other

powerful men whom the sisters had threatened to expose. 38s

e

after Anthony Comstock, who was just beginning his long career as the

self-appointed censor of the United States, realized that going after

her and her sister for publishing such sordid materials would gain him a

great deal of sympathy, both from the public at large and from the other

powerful men whom the sisters had threatened to expose. 38s

To get the goods on his quarry, Comstock had to show that Woodhull and Claflin had not merely broadcast the Beecher story in their newspaper, but had also spread the information through the U.S. mail. Consequently, having made certain that various copies of the relevant issue had been sent to his operatives, he convinced the Brooklyn District Attorney, a member of Beecher's congregation, to have Woodhull and Claflin arrested. The charges were eventually dropped, and Woodhull's version of the tale was later confirmed by Elizabeth Tilton and others, but the truth of story was buried in the countless columns of newsprint that had been devoted to it. As would happen in similar scandals thereafter, the media frenzy exhausted the public's capacity to care about the facts of the case. Nevertheless, by repeatedly arresting Woodhull and Claflin, forcing them to spend enormous sums on bail, and making sure that the details of their family history remained the talk of the town, Comstock achieved his purpose. Pursuing Woodhull and other purveyors of ostensibly corrupting information not only landed him a job as a postal inspector, and helped him to establish the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, it also led to the passage of what became known as the Comstock Law in 1873.

|

|

In the aftermath of the Beecher-Tilton

scandal, as figures such as Comstock defined the private realm as an

area that needed to be shielded from public view rather than, as Woodhull and Gilman argued, a

sphere of personal liberty, protecting individuals from embarrassment

and shame became the central focus of those who fought for the right to

privacy. And as conservatives moved to the forefront of the battle, the

right to privacy became coterminous with the right to conform to

traditional sexual mores. Sex scandals did not disappear from daily

newspapers, but the campaign waged by Comstock and others to suppress

immorality by censoring just about everything related to sexuality

effectively silenced public questioning of traditional family life.

shielded from public view rather than, as Woodhull and Gilman argued, a

sphere of personal liberty, protecting individuals from embarrassment

and shame became the central focus of those who fought for the right to

privacy. And as conservatives moved to the forefront of the battle, the

right to privacy became coterminous with the right to conform to

traditional sexual mores. Sex scandals did not disappear from daily

newspapers, but the campaign waged by Comstock and others to suppress

immorality by censoring just about everything related to sexuality

effectively silenced public questioning of traditional family life.