|

As indicated by the seal of the New York Society for the Suppression

of Vice, burning books, throwing birth control advocates in jail,

and other activities that we usually define as violations of

individual liberty were seen in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries as efforts to strengthen family government.

By

purging public culture of overt discussion of sexual matters,

censors such as Comstock sought to contain sexuality within the hierarchical confines of the

normal home.  In this conservative spirit,

"The Right to Privacy" denounced the circulation of risqué images as

an affront to public decency. As

Anita Allen and Erin Mack observe, "Brandeis and Warren's consternation about vulgar portrayals of women

stemmed from patriarchal notions of female modesty and purity," an

ideological point of origin that placed their ideas about privacy

directly in conflict with the drive toward women's independence.

41s In this conservative spirit,

"The Right to Privacy" denounced the circulation of risqué images as

an affront to public decency. As

Anita Allen and Erin Mack observe, "Brandeis and Warren's consternation about vulgar portrayals of women

stemmed from patriarchal notions of female modesty and purity," an

ideological point of origin that placed their ideas about privacy

directly in conflict with the drive toward women's independence.

41s

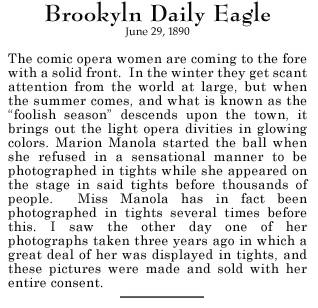

A case in point is Brandeis and Warren's favorable

mention of Manola v. Meyers & Stevens (1890), in which Marion

Manola, a well-known actress employed by a New York City opera

company, enjoined the company manager from circulating a picture

that had been surreptitiously taken during one of her performances.

Manola objected to what the

Brooklyn Eagle termed "the deadly Kodak" because it was

created without her consent and featured her wearing tights, a

costume that she apparently felt was appropriate to the stage, but

too revealing for an advertisement. 42s The Eagle agreed that Manola had every right to

stop Stevens and Meyers from exhibiting a "counterfeit of her

symmetrical physique in shop windows and other public places," and

took the company to task for asking the actress to "make an

unwomanly surrender" of her sense of propriety. As Brandeis and

Warren recount in a footnote, a preliminary injunction was issued,

and a hearing was scheduled, but Meyers & Stevens never

appeared in court. Consequently, it seemed that Manola had secured

her right to be displayed as she desired.

2p

Since Manola, who earned her own living,

successfully exerted control over the exhibition and distribution of

her own image, Manola v. Meyers has been read as a rare

moment in which an unusually independent woman realized a level of

autonomy that has traditionally been reserved to men.

43s However, given Manola's ostensible concern over the

picture as a violation of her modesty, it seems more accurate to

place this case within the context of late nineteenth-century

efforts to cleanse American culture of visible signs of sexuality. After all,

her petition to a judge to help her

to preserve some degree of respectability by limiting the public's

opportunity to ogle her body has more in common with Comstock's

contemporaneous campaign to turn the courts into "schools of public

morals" than with the struggles of women's rights activists to persuade society to

accept women as free and equal participants in public life.

44s

There is, moreover, reason to suspect that

Manola's action was not an instance in which a woman endeavored to

affirm her right to privacy, but an example of exactly the kind of

lascivious attention-getting that Warren and Brandeis found so

distasteful. To draw on language that had yet to make its way

into American vocabulary, it seems that Manola and her manager may

not have been at odds about her potential over-exposure, but were

actually trying to create some buzz. The

Eagle accordingly suggested that the public would sympathize with Manola if

the theater company thwarted her feminine sense of propriety,

unless, that is, it turned out that the injunction was a "ruse to

advertise the lady, and boom her perhaps already prepared

photographs, tights and all." A few weeks later, the Eagle

again insinuated that the entire affair was a publicity stunt,

pointing out that Manola had not previously found this glimpse

of stocking especially shocking since she had allowed similar

photographs to be taken and sold before. There is no way

to pin down Manola's real motive, but it might well have been that

the actress simply pretended to object to the picture in order to

accomplish precisely what Brandeis and Warren sought to discourage,

which was the subjection of any woman to "the reproduction of her

face, her form, and her actions, by graphic descriptions colored to

suit a gross and depraved imagination."

2p

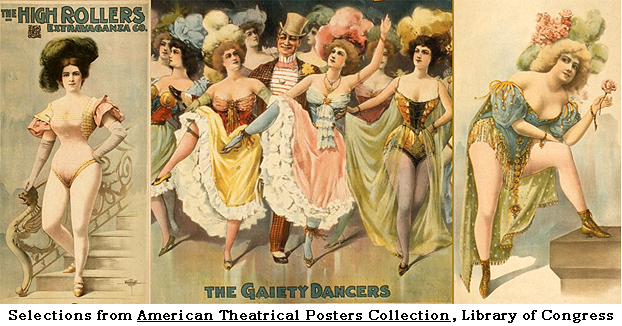

As minor as the Manola case may seem, it

illuminates the gender-based limitations of late-nineteenth century

ideas about the boundaries between public and private activities.

The right to privacy, in Brandeis and Warren's view, sheltered a

man's "personality," his intellect, emotions, thoughts, and

sensations, in other words, everything that defined him as an

individual human being. For a woman, in contrast, the right to

privacy pertained to "her face, her form, and her actions," in other

words, everything that classified her as female. Men, from

this perspective, were protected as distinct individuals, whereas

women were protected as physical types.

45s And while a man could stake a claim to his "inviolable

personality," a woman could assert her right not to be shown in an

advertisement, subjected to a physical examination, or displayed in

tights. Moreover, she could demand this right, not as a

specific person, but only as a wife, a daughter, or a mother, that

is, as a subordinate member of a family, apart from which, in the

eyes of the law, she had little or no cultural or legal identity.

Predictably, cases involving the privacy

rights of women around this time focused almost exclusively on the

unauthorized display or unwarranted exposure of their bodies.

For example, in De May v. Roberts, which was decided nearly a decade before

"The Right to Privacy" was published, Alvira Roberts filed suit

after John De May, the country doctor who attended her during childbirth,

utilized an assistant, John Scattergood, a young unmarried man who,

she later discovered, had no medical training or credentials.6p Since De May had failed to

inform either Roberts or her husband that Scattergood knew nothing

of medicine, the jury awarded Roberts $5,000. De May and

Scattergood appealed. The appeals court ruled in favor of

Roberts, asserting that a refusal to remedy such a wrong "would be

shocking to our sense of right, justice, and propriety" because "the

plaintiff had a legal right to the privacy of her apartment at such

a time." Given the "shame and mortification" of having her

person exposed to Scattergood during her "most sacred" ordeal,

Roberson was entitled to damages. 6p

De May has been interpreted as an

affirmation of Alvira Roberts' claim to "individuality and dignity,"

but, as Allen and Mack contend, reading the case as a defense of

female modesty seems closer to the mark.

46s The court, after all, did not recognize Roberts's general

right to privacy, but "a legal right to the privacy of her apartment

at such a time." Moreover, that Scattergood had no medical

training seemed irrelevant in relation to Roberts's health, but it

did matter --as did the fact that he was a young unmarried man--in

relation to her status as a married woman, which according to the

law and prevailing standards of decency, limited access to her body

to her husband and, in the words of the court, "medical men."

Consequently, having held Roberts's hand during a paroxysm of labor,

Scattergood had, the court ruled, "indecently, wrongfully and

unlawfully laid hands upon and assaulted her."

Meanwhile, De May's offense, as the court recounted in an outraged

tone, was that the doctor had wrongly invited Scattergood into the

Roberts home when he should have known that the young man would be

able to "hear...if not see all that was said and done." Thus,

at the very moment that Anthony Comstock was busy purging American

culture of all explicit references to sex and contraception, De

May suggested that child birth is "sacred" when assisted by the

right people, but when it is witnessed by "intruders," it becomes

obscene.

In 1891, in

Union Pacific Railway

Company v. Botsford, the Supreme Court adopted a similarly

protective approach to the female body. Clara Botsford was

sleeping on a train when the berth above her collapsed, hit her on

the head, and caused "permanent and increasing injuries."7p She

sued the railway company for negligence and received a $10,000

reward. Since the company had requested that Botsford submit

to a physical examination by her own doctor, and Botsford had

refused even though the defendant had promised "not to expose the

person of the plaintiff in any indelicate manner," Union Pacific

appealed. To show that Botsford's refusal was legitimate,

Justice Gray did not explicitly mention the right to privacy, but he

followed Brandeis and Warren's example by citing Thomas Cooley's

declaration that "the right to one's person

may be said to be a right of complete immunity: to be let alone."

37s Moreover, like Brandeis and Warren, the Court

stressed that the "inviolability" of the body was particularly

"sacred" in cases involving women.

The inviolability of the person is as much invaded by a compulsory

stripping and exposure, as by a blow. To compel anyone, and

especially a woman, to lay bare the body, or to submit it to the

touch of a stranger, without lawful authority, is an indignity, an

assault and a trespass.

7p

A few months later, in the first round of

Schuyler v. Curtis (1891), which specifically addressed a

woman's right to privacy, the New York State Supreme Court

explicitly endorsed Brandeis and Warren's arguments.8p The

dispute arose after a women's group planned to commission a statue

of the late Mrs. George Schuyler, a philanthr opist,

at the Columbian Exhibition, which was scheduled to open in Chicago

in 1893. Philip Schuyler, Mrs. Schuyler's nephew, sought an

injunction against the statue on several grounds including his late

aunt's distaste for any type of notoriety and her disapproval of the

views of Susan B. Anthony, who was supposed to be memorialized with

a similar statue that was to placed nearby. In affirming the

preliminary injunction, Justice Morgan O'Brien did not focus

on Philip Schuyler's insistence that his aunt would have been

mortified to find herself exhibited next to Anthony, whom the judge

described as a "well-known agitator."8p Instead, O'Brien's

comments addressed the defendants' contention that Mrs. Schuyler's

status as a public figure extinguished her relatives' right to

intervene. opist,

at the Columbian Exhibition, which was scheduled to open in Chicago

in 1893. Philip Schuyler, Mrs. Schuyler's nephew, sought an

injunction against the statue on several grounds including his late

aunt's distaste for any type of notoriety and her disapproval of the

views of Susan B. Anthony, who was supposed to be memorialized with

a similar statue that was to placed nearby. In affirming the

preliminary injunction, Justice Morgan O'Brien did not focus

on Philip Schuyler's insistence that his aunt would have been

mortified to find herself exhibited next to Anthony, whom the judge

described as a "well-known agitator."8p Instead, O'Brien's

comments addressed the defendants' contention that Mrs. Schuyler's

status as a public figure extinguished her relatives' right to

intervene.

While acknowledging Mrs. Schuyler's

magnanimity, O'Brien

emphasized that she was not a public figure because she had always exercised her generosity in an "unobtrusive way."

Then, after reciting Philip Schuyler's declaration that his aunt's

"great refinement and cultivation" had led her shun all forms of

publicity, the judge quoted at length from "The Right to Privacy."

"In a recent of the Harvard Law Review," O'Brien wrote, "we

find an able summary of the extension and development of the law of

individual rights, which well deserves and will repay the perusal of

every lawyer." O'Brien reiterated Brandeis and Warren's call for

control over the circulation of personal portraits, noted that

Godkin had provided similar justifications, and observed that the

individual's right to prevent certain types of public disclosure had

been confirmed in the Manola case. The examples cited by

Brandeis and Warren, especially Prince Albert v. Strange, signaled,

O'Brien concluded, "a clear recognition...of the principle that the

right to which protection is given is the right to privacy."

8p

In 1895, when the

New York Court of Appeals finally

decided the case, Philip Schuyler lost.9p The court did not

deny the existence of a right to privacy, nor did it deny that

damages may be rewarded to recognize the genuine distress endured by

victims of privacy violations. Rather, the court held that

whatever right to privacy Mrs. Schuyler may have enjoyed during her

life, it died

when she did, as did any legal consideration of what her feelings

might have been about having her likeness displayed in a public

place. The court also firmly rejected the plaintiff's

contention that his aunt would not have wanted to be displayed

alongside Susan B. Anthony. Whatever Mrs. Schuyler's opinions

may have been, the court took time to argue, no reasonable person

could object to being associated with Anthony, even if that person

did not share her ideas about women's participation in public life:

The fact, if it be a fact, that Mrs. Schuyler did not sympathize

with what is termed the "Woman's Rights" movement is of no

importance here... Many of us may, and probably do, totally

disagree with these advanced views of Miss Anthony in regard to

the proper sphere of women, and yet it is impossible to deny to

her the possession of many of the ennobling qualities which tend

to the making of great lives.

9p

The

Schuyler court's tension-filled comments on Anthony remind us

that the original assertion of the right to privacy unfolded at a time

when the term "Women's Rights" was still far enough from popular

acceptance to require capitalization and quotation marks.

Moreover, as noted in this opinion, the point at issue in the struggle

for sexual equality was 'the proper sphere of women.' While

advocates for equality such as Anthony were distinguished by their

unusual willingness to live "in the face of the whole world," even

relatively

prominent women such as Schuyler were still expected to at least try

to avoid public

attention. The court accordingly stressed that a "shy,

sensitive, retiring woman might naturally be extremely reluctant to

have her praises sounded, or even appropriate honors accorded her

while living,"

but the principle that death extinguishes all claims to individual

rights "applies as well to the most

refined and retiring woman as to a public man." 9p

Go to page 7: Privacy and Publicity in the

Early Twentieth Century

|