|

Course Material for Media & Politics Professor Susan E. Gallagher, UMASS Lowell Originally posted 12/04; updated 9/05

Flood the Zone With Innuendo: Walter V. Robinson's Approach to the News

In some cases, as in his first series of articles on apparent gaps in President George W. Bush's performance of his duties while serving in the Texas Air National Guard, Robinson focused relatively squarely on documentary records and factual accounts. In others, he strayed into the far more slippery terrain of psychological profiling. In front-page portraits of former vice president Al Gore, former Boston mayor Ray Flynn, civil rights leader Paul Parks, and historian Joseph Ellis, Robinson went beyond pointing out inconsistencies between the claims that each of these men had made about himself and what each had actually done. He called in psychologists to speculate about their motivations and summarized the thoughts of vaguely defined groups of people instead of relaying what specific individuals had actually said.

Though it might seem like a short step from showing that someone has lied to portraying that person as a liar, a review of Robinson's work over the years illustrates that this shift can transform the writing of a story into a profound abuse of power. That is, when Robinson's aim has been not to expose contradictions, but to promote particular judgments, his reporting exhibits precisely the characteristics that he attributes to his targets, namely, a tendency to embellish, exaggerate, and stretch the truth to suit his purpose. Moreover, whereas Gore, Flynn, Parks, and Ellis had all, according to Robinson, twisted facts in the interest of self-promotion, Robinson engaged in what is usually seen as a much more egregious form of deception by vandalizing other people's lives. It is, after all, hard to determine who is harmed when public figures such as Gore, Ellis, Parks, and Flynn commit the sin of self-aggrandizement, but Robinson's misleading reporting on both well-known and ordinary people has ended careers, ruined reputations, inflicted deep humiliation, and, at least in the case of clergy sex abuse victim Paul R. Edwards, by far the most vulnerable addition to Robinson's roster, brought a blameless man to the brink of suicide.

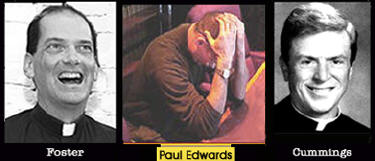

Robinson's demolition of Edwards, which ensued after Edwards charged Monsignor Michael Smith Foster, a powerful canon lawyer, and the late Rev. William J. Cummings, with sexual misconduct, stands out both for its viciousness and for its magnitude: Robinson and his allies at the Globe assaulted Edwards' character and credibility in over twenty inaccurate articles, and the paper's editors, reporters, and ombudsman uniformly ignored repeated calls for corrections from victim advocacy groups. However, what is most striking about Robinson's blitzkrieg against Edwards is not its anomalous aspects, but how closely it resembles his previous attacks. Indeed, what becomes obvious when the Edwards story is placed against the backdrop of Robinson's campaigns against more prominent people is that his smears usually rely on a few well-worn devices, a set of journalistic sleights of hand that allow him to undermine his targets without having to depend on verifiable facts.

Unlike former Globe intern and New York Times reporter Jayson Blair, who gave his counterfeit articles an air of authenticity by inventing atmospheric details, or former Globe columnist Patricia Smith, who nearly won a Pulitzer for making up emotionally riveting people, or former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who attempted to enhance his hilarity by copying jokes from a book that he claimed he had not read, Robinson achieves his ends by omission, distortion, and repetition, techniques that slant the truth but make it difficult to catch him in an outright lie.

Surveying Robinson's deployment of these techniques between the early 1980's, when a jury found that one of his articles contained a substantial amount of false information, and 2003, when he collected the Pulitzer Prize, does not explain why he has labored to destroy so many people. However, it sheds some light on the indifference to the truth that has historically plagued the Globe's internal culture, and it also shows how dangerous it can be when journalists attempt to score points by playing up preconceived ideas about their subjects' psychological tendencies.

Back to main page Go to page two

|