|

In 1928, in his famous dissent in

Olmstead v. United States (1928),

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis crowned the right to privacy as

the core value in American life.1p "The makers of our

Constitution," Brandeis declared, "sought to protect Americans in their

beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They

conferred, as against the Government, the right to be let alone -- the

most comprehensive of rights, and the right most valued by civilized

men."1p Brandeis's ringing tribute may have been on the losing

side in the 1920's, but since then Americans have increasingly come to

share his view of the right to be let alone as the key to individual

dignity, autonomy, and fulfillment.1s Indeed, in our time,

commitment to the right to privacy shapes debate on everything from

media analysis to medical treatment.2s Meanwhile, calls to shift governmental

functions from the public sphere, which is usually associated in this

discourse with incompetence, waste, and stagnation, to the private

realm, which is typically linked with resourcefulness, efficiency, and

progress, have grown apace.3s

Rather than attempting to explain how Americans came to put such a

premium on private activities or why we seem less and less inclined to

participate in public affairs, this essay presents a snapshot of the

historical moment when the right to privacy was first recognized as

a fundamental principle of American law. By locating the

arguments

that Brandeis and his law partner, Samuel Warren, advanced in

"The Right to Privacy" (1890)

2p

within the social and political landscape of the late nineteenth century,

I hope to show that the valorization of private life that is so evident

in postmodern American society began as what may be described, to

borrow a phrase that has been used in other contexts, as a revolt

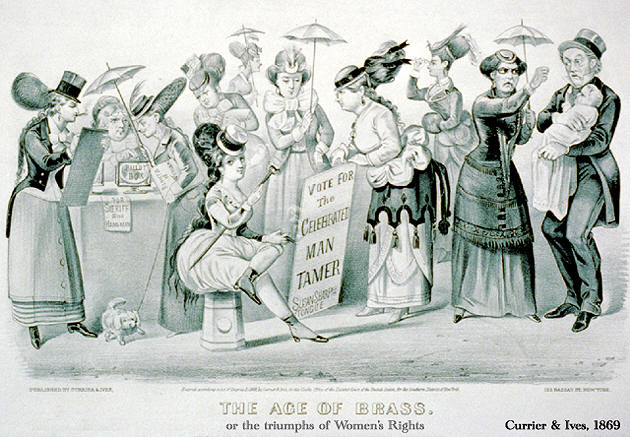

against modernity.4s While this revolt

can be generally defined as a reaction against the rise of industrial

capitalism, it can be more specifically understood an attempt to

preserve the traditional family from the unsettling effects of the

women's rights movement and from the invasive aspects of mass

culture, especially as

embodied in the popular press.

Many other scholars have drawn attention to

the conservative, patrician, and patriarchal standpoint of "The Right

to Privacy." 5s Taking

these works, most notably, Anita Allen and Erin Mack's "How Privacy

Got Its Gender," as my starting point, I try to place Brandeis and

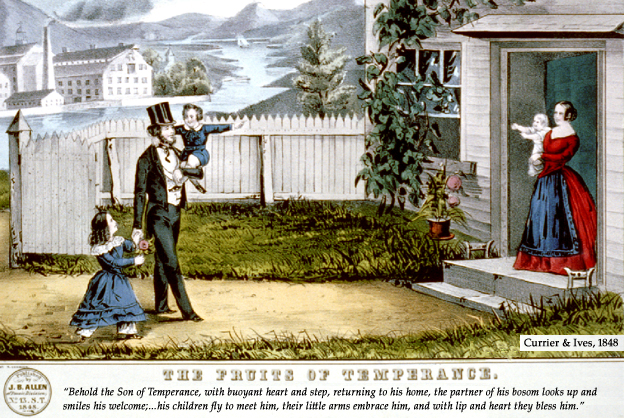

Warren's article even more concretely within the cult of domesticity

that consumed American society in the decades after the Civil War.6s What becomes clear when "The Right to Privacy" is set

directly within the flood of

lithographs, advice books, advertisements, newspaper editorials,

political tracts, and legal rulings that idealized the family

throughout this era is that Brandeis and Warren were not mapping out

an area in which individuals--male or female--could exercise some type

of freedom of choice. In the late nineteenth century, the

private realm was almost never seen as a space in which individuals enjoy a significant

degree of liberty.7s Instead,

marching in lockstep with contemporary celebrations of the family, "The Right to Privacy" equated the

private sphere with the traditional family circle, an arena in which individuals

were expected to find fulfillment, not by choosing among various modes

of behavior, but by bending to the discipline inherent in the

hierarchy of the

home.

Placing Brandeis and Warren's work within its historical context also

shows that the public/private

dichotomy did not, in its original iteration, draw a boundary between political coercion and

individual freedom. On the contrary, in nineteenth-century American culture and

legal theory, the public usually signified the world of social

climbing, economic conflict,

and political one-upmanship. The private, on the

other hand, referred to that part of life in which human beings meet

(or fail to meet) their moral obligations. Whereas classical European versions of the

public/private split revolve around the distinctions between

state and family, politics and biology, reason and passion,

citizenship and self-interest, freedom and necessity, the

public/private dichotomy in the United States, at least as it emerged

near the end of the late nineteenth-century, provides yet more

evidence of American exceptionalism.8s

As indicated by the anti-political sentiments expressed by

Brandeis and subsequent champions of the right to privacy,

the political process at least in times of relative peace, appears in the

American intellectual tradition, not as an expression of our capacity

engage in the vita activa, but as a largely superficial system in which

self-interested groups and individuals scramble for pieces of pie. 9s

Brandeis and Warren accordingly defended the private realm as an asylum from the

whole of modern society and did not even single out government from other ostensibly distasteful

features of modernity

such as mass entertainment and

yellow journalism.

Meanwhile, by celebrating the domestic sphere as the area in

which each man develops his "inviolable personality" or, as Brandeis later put it in Olmstead,

his "spiritual nature," "feelings," and "intellect," they set up the family as the site of

authentic experience. The private/public dichotomy, from this

peculiarly American standpoint, pits the moral reality of the family

against the hollow and frequently corrupting spectacle of business, politics, and

social frivolity. In short, for Brandeis and Warren, the family

home was the genuine center of human existence, and everything else was just the

shallow world outside.

In order to comprehend how the right to privacy evolved over the

course of the twentieth century, it is, therefore, necessary first to

locate its origins in late nineteenth-century anxieties about the ways

in which the forces of modernity seemed to threaten the order of family

life. What we shall see if we set aside

more recent tendencies to conflate privacy and freedom is that

Brandeis and Warren wrote "The Right to Privacy," not because they

felt that the conditions of modern industrial society were impinging

on individual liberty, but because they believed that these conditions

had made it increasingly difficult for individuals to practice the

discipline required to discharge properly their particular duties as fathers, mothers,

daughters, sons, sisters, brothers, husbands, and wives.

Go to page 2: The Anxieties of Exposure

|