Section 14.4 The Monoid of a Finite-State Machine

In this section, we will see how every finite-state machine has a monoid associated with it. For any finite-state machine, the elements of its associated monoid correspond to certain input sequences. Because only a finite number of combinations of states and inputs is possible for a finite-state machine there is only a finite number of input sequences that summarize the machine. This idea is illustrated best with a few examples.

Consider the parity checker. The following table summarizes the effect on the parity checker of strings in \(B^1\) and \(B^2\text{.}\) The row labeled “Even” contains the final state and final output as a result of each input string in \(B^1\) and \(B^2\) when the machine starts in the even state. Similarly, the row labeled “Odd” contains the same information for input sequences when the machine starts in the odd state.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c|cccccc}

\textrm{ Input} \textrm{ String} & 0 & 1 & 00 & 01 & 10 & 11 \\

\hline

\textrm{ Even} & (\textrm{ Even},0) & (\textrm{ Odd},1) & (\textrm{ Even},0) & (\textrm{ Odd},1) & (\textrm{ Odd},1) & (\textrm{ Even},0) \\

\textrm{ Odd} & (\textrm{ Odd},1) & (\textrm{ Even},1) & (\textrm{ Odd},1) & (\textrm{ Even},1) & (\textrm{ Even},0) & (\textrm{ Odd},1) \\

\textrm{ Same} \textrm{ Effect} \textrm{ as} & & & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

Note how, as indicated in the last row, the strings in \(B^2\) have the same effect as certain strings in \(B^1\text{.}\) For this reason, we can summarize the machine in terms of how it is affected by strings of length 1. The actual monoid that we will now describe consists of a set of functions, and the operation on the functions will be based on the concatenation operation.

Let \(T_0\) be the final effect (state and output) on the parity checker of the input 0. Similarly, \(T_1\) is defined as the final effect on the parity checker of the input 1. More precisely,

\begin{equation*}

T_0(\textrm{ even})=(\textrm{ even},0) \quad \textrm{and} \quad T_0(\textrm{ odd})=(\textrm{ odd},1)\textrm{,}

\end{equation*}

while

\begin{equation*}

T_1(\textrm{ even})=(\textrm{ odd},1) \quad \textrm{and} \quad T_1(\textrm{ odd})=(\textrm{ even},0)\textrm{.}

\end{equation*}

In general, we define the operation on a set of such functions as follows: if \(s\text{,}\) \(t\) are input sequences and \(T_s\) and \(T_t\text{,}\) are functions as above, then \(T_s*T_t=T_{st}\text{,}\) that is, the result of the function that summarizes the effect on the machine by the concatenation of \(s\) with \(t\text{.}\) Since, for example, 01 has the same effect on the parity checker as 1, \(T_0*T_1=T_{01}=T_1\text{.}\) We don’t stop our calculation at \(T_{01}\) because we want to use the shortest string of inputs to describe the final result. A complete table for the monoid of the parity checker is \(\begin{array}{c|c}

* &

\begin{array}{cc}

T_0 & T_1 \\

\end{array}

\\

\hline

\begin{array}{c}

T_0 \\

T_1 \\

\end{array}

&

\begin{array}{cc}

T_0 & T_1 \\

T_1 & T_0 \\

\end{array}

\\

\end{array}\)

What is the identity of this monoid? The monoid of the parity checker is isomorphic to the monoid \(\left[\mathbb{Z}_2; +_2\right]\text{.}\)

This operation may remind you of the composition operation on functions, but there are two principal differences. The domain of \(T_s\) is not the codomain of \(T_t\) and the functions are read from left to right unlike in composition, where they are normally read from right to left.

You may have noticed that the output of the parity checker echoes the state of the machine and that we could have looked only at the effect on the machine as the final state. The following example has the same property, hence we will only consider the final state.

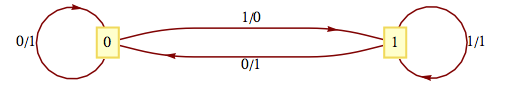

The transition diagram for the machine that recognizes strings in \(B*\) that have no consecutive 1’s appears in Figure 14.4.2. Note how it is similar to the graph in Figure 9.1.4. Only a “reject state” has been added, for the case when an input of 1 occurs while in State \(a\text{.}\) We construct a similar table to the one in the previous example to study the effect of certain strings on this machine. This time, we must include strings of length 3 before we recognize that no “new effects” can be found.

\(\begin{array}{ccccccccccccccc}

\textrm{ Inputs} & 0 & 1 & 00 & 01 & 10 & 11 & 000 & 001 & 010 & 011 & 100 & 101 & 110 & 111 \\

s & b & a & b & a & b & r & b & a & b & r & b & a & r & r \\

a & b & r & b & a & r & r & b & a & b & r & r & r & r & r \\

b & b & a & b & a & b & r & b & a & b & r & b & a & r & r \\

r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r & r \\

\textrm{ Same} \textrm{ as} & & & 0 & & & & 0 & 01 & 0 & 11 & 10 & 1 & 11 & 11 \\

\end{array}\)

The following table summarizes how combinations of the strings \(0,1,01,10, \textrm{ and } 11\) affect this machine.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c|c}

* &

\begin{array}{ccccc}

T_0 & T_1 & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\end{array}

\\

\hline

\begin{array}{c}

T_0 \\

T_1 \\

T_{01} \\

T_{10} \\

T_{11} \\

\end{array}

&

\begin{array}{ccccc}

T_0 & T_1 & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_{11} & T_1 & T_{11} & T_{11} \\

T_0 & T_{11} & T_{01} & T_{11} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_1 & T_1 & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{11} & T_{11} & T_{11} & T_{11} & T_{11} \\

\end{array}

\\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

All the results in this table can be obtained using the previous table. For example,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c}

T_{10}*T_{01}=T_{1001}=T_{100}*T_1=T_{10}*T_1=T_{101}=T_1\\

\textrm{ and} \\

T_{01}*T_{01}=T_{0101}=T_{010}T_1=T_0T_1=T_{01}\\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

Note that none of the elements that we have listed in this table serves as the identity for our operation. This problem can always be remedied by including the function that corresponds to the input of the null string, \(T_{\lambda }\text{.}\) Since the null string is the identity for concatenation of strings, \(T_sT_{\lambda }=T_{\lambda }T_s=T_s\) for all input strings \(s\text{.}\)

Example 14.4.3. The Unit-time Delay Machine.

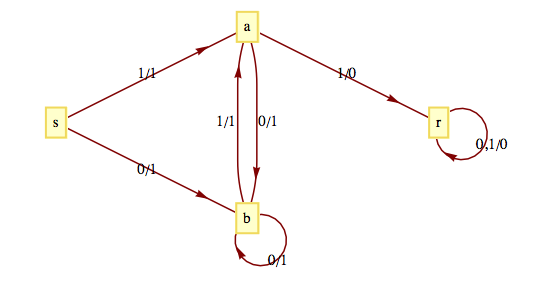

A finite-state machine called the unit-time delay machine does not echo its current state, but prints its previous state. For this reason, when we find the monoid of the unit-time delay machine, we must consider both state and output. The transition diagram of this machine appears in Figure 14.4.4.

\(\begin{array}{c|c}

\textrm{ Input} &

\begin{array}{cccccccccc}

&

\begin{array}{cc}

0 & 1 \\

\end{array}

& 00\textrm{ } & 01\textrm{ } & \textrm{ }10\textrm{ } & 11 & 100\textrm{ or}000\textrm{

} & 101\textrm{ or}001 & 110\textrm{ or}101 & 111\textrm{ or}011 \\

\end{array}

\\

\hline

\begin{array}{c}

0 \\

1 \\

\textrm{ Same} \textrm{ as} \\

\end{array}

&

\begin{array}{cccccccccc}

(0,0) & (1,0) & (0,0) & (1,0) & (0,1) & (1,1) & (0,0) & (1,0) & (0,1) & (1,1) \\

(0,1) & (1,1) & (0,0) & (1,0) & (0,1) & (1,1) & (0,0) & (1,0) & (0,1) & (1,1) \\

& & & & & & 00 & 01 & 10 & 11 \\

\end{array}

\\

\end{array}\)

Again, since no new outcomes were obtained from strings of length 3, only strings of length 2 or less contribute to the monoid of the machine. The table for the strings of positive length shows that we must add \(T_{\lambda }\) to obtain a monoid.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c|c}

* &

\begin{array}{cccccc}

T_0 & T_1 & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\end{array}

\\

\hline

\begin{array}{c}

T_0 \\

T_1 \\

T_{00} \\

T_{01} \\

T_{10} \\

T_{11} \\

\end{array}

&

\begin{array}{cccccc}

T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\end{array}

\\

\end{array}\text{.}

\end{equation*}

Exercises Exercises

1.

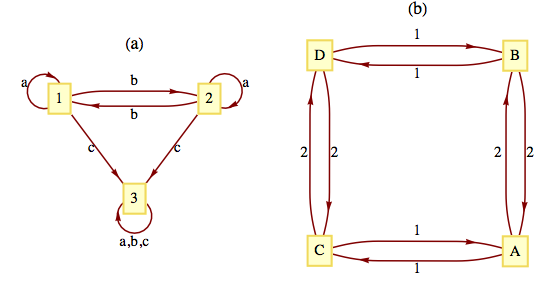

For each of the transition diagrams in Figure 5, write out tables for their associated monoids. Identify the identity in terms of a string of positive length, if possible.

Hint.

Answer.

Where the output echoes the current state, the output can be ignored.

-

\(\begin{array}{c|cccccc} \textrm{ Input String} & a & b & c & aa & ab & ac \\ \hline 1 & (a,1) & (a,2) & (c,3) & (a,1) & (a,2) & (c,3) \\ 2 & (a,2) & (a,1) & (c,3) & (a,2) & (a,1) & (c,3) \\ 3 & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) \\ \end{array}\) \(\begin{array}{c|cccccc} \textrm{ Input String} & ba & bb & bc & ca & cb & cc \\ \hline 1 & (a,2) & (a,1) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) \\ 2 & (a,1) & (a,2) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) \\ 3 & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) & (c,3) \\ \end{array}\)We can see that \(T_aT_a= T_{\textrm{ \textit{aa}}}=T_a\text{,}\) \(T_aT_b= T_{\textrm{ \textit{ab}}}= T_b\text{,}\) etc. Therefore, we have the following monoid:\begin{equation*} \begin{array}{c|c} & \begin{array}{ccc} T_{a} & T_b & T_b \\ \end{array} \\ \hline \begin{array}{c} T_a \\ T_b \\ T_c \\ \end{array} & \begin{array}{ccc} T_a & T_b & T_c \\ T_b & T_a & T_c \\ T_c & T_c & T_c \\ \end{array} \\ \end{array} \end{equation*}Notice that \(T_a\) is the identity of this monoid.

-

\(\begin{array}{c|cccccc} \textrm{Input String} & 1 & 2 & 11 & 12 & 21 & 22 \\ \hline A & C & B & A & D & D & A \\ B & D & A & B & C & C & B \\ C & A & D & C & B & B & C \\ D & B & C & D & A & A & D \\ \end{array}\)\(\begin{array}{c|cccccccc} \textrm{Input String} &111 & 112 & 121 & 122 & 211 & 212 & 221 & 222 \\ \hline A & C & B & B & C & B & C & C & B \\ B & D & A & A & D & A & D & D & A \\ C & B & C & C & B & C & B & B & C \\ D & B & C & C & B & C & B & B & C \\ \end{array}\)We have the following monoid:\begin{equation*} \begin{array}{c|c} & \begin{array}{cccc} T_1 & T_2 & T_{11} & T_{12} \\ \end{array} \\ \hline \begin{array}{c} T_1 \\ T_2 \\ T_{11} \\ T_{12} \\ \end{array} & \begin{array}{cccc} T_{11} & T_{12} & T_1 & T_2 \\ T_b & T_{11} & T_2 & T_1 \\ T_1 & T_2 & T_{11} & T_{12} \\ T_2 & T_1 & T_{12} & T_{11} \\ \end{array} \\ \end{array} \end{equation*}Notice that \(T_{11}\) is the identity of this monoid.

2.

What common monoids are isomorphic to the monoids obtained in the previous exercise?

3.

Can two finite-state machines with nonisomorphic transition diagrams have isomorphic monoids?

Answer.

Yes, just consider the unit time delay machine of Figure 14.4.4. Its monoid is described by the table at the end of Section 14.4 where the \(T_{\lambda

}\) row and \(T_{\lambda }\) column are omitted. Next consider the machine in Figure 14.5.7. The monoid of this machine is:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

& T_{\lambda } & T_0 & T_1 & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\hline

T_{\lambda } & T_{\lambda } & T_0 & T_1 & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\hline

T_0 & T_0 & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_1 & T_1 & T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{00} & T_{00} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{01} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{10} & T_{10} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

T_{11} & T_{11} & T_{10} & T_{11} & T_{00} & T_{01} & T_{10} & T_{11} \\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

Hence both of these machines have the same monoid, however, their transition diagrams are nonisomorphic since the first has two vertices and the second has seven.